5e Congrès de la LILA, Genève 1952

Par Barbara Kaye Muir

Barbara Kaye était une romancière et l'épouse du deuxième président de la LILA Percy H. Muir. Publié dans "Second Impression. Rural Life with a Rare Bookman" (Oak Knoll Press 1995).

It felt strange to arrive in Geneva and not be greeted by William Kundig. Instead, it was Nicholas Rauch, president of the Swiss association, who hat attended the London conference, who welcomed us to the league's fifth annual meeting. William had died from a heart attack while in the United States earlier this year. …

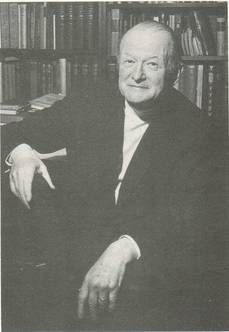

The Swiss had chosen to hold the conference at the end of July, which meant that Percy and I had hardly got our breath back after our German trip before we were off again, although this time for only six days. It was to be Percy's last conference as president. He had done his best to persuade André (Poursin) to step into his shoes, as the obvious and best possible successor, but André had insisted that Georges Blaizot was the man for the job (it was time to have a French president) and had undertaken to persuade him to stand. Failing André, Percy was happy to hand over to the quiet, courteous Georges.

The weather was brilliant. We had arrived on the Saturday evening and booked into the Hotel du Rhone, where the conference was being held and most of the executive were staying. It was too big and too grand for my taste; flunkeys - and there were plenty - unnerve me. The conference was to open on the Monday morning, preceded by a "Vin d'honneur" to which our hosts had cordially invited "Les Dames" as well. This being Switzerland, where women still did not have the vote, the invitation assumed that the delegates would all be "les Messieurs," which they were not.

The weather was brilliant. We had arrived on the Saturday evening and booked into the Hotel du Rhone, where the conference was being held and most of the executive were staying. It was too big and too grand for my taste; flunkeys - and there were plenty - unnerve me. The conference was to open on the Monday morning, preceded by a "Vin d'honneur" to which our hosts had cordially invited "Les Dames" as well. This being Switzerland, where women still did not have the vote, the invitation assumed that the delegates would all be "les Messieurs," which they were not.

We awoke on the Sunday morning to a picture postcard scene. The hotel stood where the fast-flowing waters of the Rhone spill down into the great, wide-spreading lake of Geneva, so that the cool shush-shush of rushing water greeted arrivals and departures and could be heard in the bedroom if one opened the windows. White sails dotted the lake; houses along the shore looked like cut-outs against an azure sky. Percy, as usual, had to chair a pre-conference committee meeting. I was free. The morning was mine to spend as I fancied.

Later, when the rest of the delegates arrived, there would be the greetings and embraces, the babel of voices in different tongues, the cigarette smoke (we were all smokers in those days), the heat, the drinking, and the long-drawn-out meals. But first I would go out walking alone.

"Don't be late, then," said Percy. "We'll all be lunching here after the committee."

I promised not to be and set off in my sandals and cotton dress, bare-legged (I could change on my return for the smart luncheon party) with a few Swiss francs in any pocket - just in case. I had walked along the lakeside on previous visits. For a change I turned inland, thinking I would have a look at the part of the city away from the smart shops and hotels, where the not-so-smart people lived. For a young (well, youngish) foreign woman to walk alone in downtown Geneva on a Sunday morning could hardly be called risky. I didn't expect to be pursued by lustful young males, as I might have been in Italy, as I walked along tree-lined streets of neat houses, passing an occasional school or grey parish church, with the cars of the devout parked nearby. It was all very quiet, tidy, and rather boring. ...

The committee meeting was over; Percy and André and the other members with a couple of the wives were on the terrace drinking wine when I joined them. Someone offered to get me a glass. "Thanks," I said, "but I won't have any more just now. I've been drinking with a Swiss sailor." They all laughed, and no one believed me.

It was a successful conference. The ABA, under the chairmanship of Stanley Sawyer, had had second thoughts on pressing for a reduction of the subscription, and unanimity prevailed on all important decisions. The entry of Germany into the league, with its large membership, meant that a supplement to the directory was needed. Once again the time-consuming and unpaid job of sorting and editing the entries fell to Percy and André. For the League, this meant further income from advertising revenue as well as a boost for the directory's sales in Germany. This was the good news. The disappointing news was that the other important project, the dictionary of terms taken on by Hertzberger in Copenhagen, had still to be completed.

The German delegation was led this time by Ernst Hauswedell, who ran an international book and fine arts auction business in Hamburg. Like Helmuth he spoke excellent English. He was a charming, highly civilized man, with an imperturbable manner that never faltered, a characteristic of successful auctioneers.

The German delegation was led this time by Ernst Hauswedell, who ran an international book and fine arts auction business in Hamburg. Like Helmuth he spoke excellent English. He was a charming, highly civilized man, with an imperturbable manner that never faltered, a characteristic of successful auctioneers.

He was known to have a weakness for pretty women and had come to the conference with his very pretty new wife, Waldtraut, who had been someone else's wife not long before. According to a story going the rounds, a member of her family had come to one of Ernst's auctions and jumping up in the middle of the sale had pointed his finger at Ernst, shouting the accusation: "Adulterer!" Without turning a hair, so the story went, Ernst had calmly continued to take bids for the lot he was selling.

Already there were rumblings of disagreement in the ranks of the German dealers over the alleged domination of the trade by the larger firms, many of whom also ran auctions. Unlike in Britain there was not the clear distinction in Germany between auction houses and antiquarian booksellers. Eventually, the quarrel reached the point when, failing agreement between the two sides (the Verband, to which the auction houses belonged, and the Vereinigung, representing mainly the smaller dealers), Germany temporarily had no representation in the League. Invited by both sides to act as honest broker, Percy would make a trip to Germany to try to achieve a compromise, "an almost impossible task," he declared. But some good did come of his efforts, and the problem of representation in the League was eventually solved.

The Swiss had arranged a couple of treats for us; we were taken for a cruise on the lake, with luncheon aboard, on the first afternoon, disembarking for a stroll in the Jardin Anglais, regarded by the British as a charming, unspoken compliment. Later in the week there was a visit to the private library of Martin Bodmer, a Swiss collector whose name was known to the rare book trade worldwide. This was a very different affair from the never-to-be-forgotten Foyle outing. Everyone behaved impeccably, gazing respectfully with polite murmurs of admiration at the fabulous collection of fine volumes and rarities displayed for our benefit. Not a few of these had no doubt been acquired from some of those present. Promptly at six o'clock the party ended, and we were returned sober and suitably impressed to our respective hotels.

The Swiss ladies' committee opted for safety, as we had in London, and the and the special event for les dames was tea on the terrace of one of the smart department stores. Very sensibly this time there was no press photo call. With the program curtailed to four days we were all less exhausted and in better shape than at previous conferences for the grand finale - the traditional farewell dinner and dance.

At the final session of the assembly Percy had kept to his declared resolve and duly stepped down from the office of president. He had then unanimously been voted President of Honor no altogether to his surprise.

At the final session of the assembly Percy had kept to his declared resolve and duly stepped down from the office of president. He had then unanimously been voted President of Honor no altogether to his surprise.

It was a position he was quite willing to accept; he was not yet ready to retire to the sidelines, and it allowed him to continue to work with the committee and use his influence in shaping the league's future. A time would come when he would feel that his counsel was no longer wanted by the younger members, but that was some years away. It was on his proposal that André, a vice president from the formation, was also voted a President of Honour.

Einar Gronholt-Pedersen, another of the old guard who had served his term of office, was persuaded to stay on for another three years without too much difficulty - to everyone's satisfaction - but Menno was not to be persuaded to do the same. Behind the scenes the question of what to do about Menno had been exercising the minds of the rest of the committee. As the man who had thought up the idea of the league, he could hardly be allowed to retire without some sort of official recognitions or accolade.

"Why not invent a new office and nominate him Father of the League?”, suggested someone. This was hailed as a splendid solution; the title should, it was agreed, confer ex-officio status, which would please Menno (if not everyone else), and it would be non-perpetuating. Duly proposed by Georges Blaizot at the final session of the assembly, it was agreed by acclaim. The vacancy caused by Menno's retirement from the committee was then filled by the election of the past president of the Italian association, Dr. Aeschlimann, a quiet scholarly man who gave the impression of being somewhat remote from events but was well liked and already a familiar face at conferences, with his equally quiet intellectual wife, who composed music, but of what kind I never discovered.

"Why not invent a new office and nominate him Father of the League?”, suggested someone. This was hailed as a splendid solution; the title should, it was agreed, confer ex-officio status, which would please Menno (if not everyone else), and it would be non-perpetuating. Duly proposed by Georges Blaizot at the final session of the assembly, it was agreed by acclaim. The vacancy caused by Menno's retirement from the committee was then filled by the election of the past president of the Italian association, Dr. Aeschlimann, a quiet scholarly man who gave the impression of being somewhat remote from events but was well liked and already a familiar face at conferences, with his equally quiet intellectual wife, who composed music, but of what kind I never discovered.

While everyone was congratulating Blaizot on his unanimous election as president, poor Ingelese was in tears, sobbing that we were all trying to kill her husband. It was true that as a diabetic Georges' health was not good, yet ironically it was Ingelese who would die in a very few years, tragically young, while Georges lived until 1976.

With Percy now an ex-officio member of the executive, Stanley Sawyer was voted on to the committee in his place and quickly became known as "John Bull," a nickname he accepted in good part, even signing himself "John Bull" on my menu card at the farewell dinner. Sturdy and stubborn, refusing to speak any language save his own, he admittedly did conform to the continental idea of a typical Briton. But at the same time he was a man to inspire affection, being completely unpompous and possessed of a strong sense of humor. In common with Dudley Massey, another hopeless linguist, he seldom travelled abroad without joy, his French-speaking wife, who was much admired by André.

An innovation at the Geneva conference was the book exhibition and sale (including stamps) organized by the Syndicat Suisse in Nicholas Rauch's auction room during the conference week. The businesslike Swiss had thought it only sensible to offer their guests (two hundred delegates from the thirteen countries) the opportunity to buy a few books from Syndicat members based in other parts of the country as well as from those in Geneva.

Nicholas Rauch had by this time taken over Kundig's business. He was a very different character from William, with a quiet pleasant manner and none of William's showmanship. He had an attractive, vivacious wife, who, like most of the educated Swiss we met, spoke good English. As host and hostess, both were indefatigable in making the four days a success. Alas, before very long we would hear that Lucy Rauch had died of cancer. Nicholas would die of the same disease not so long after.

Our hosts kept us so well lubricated at the farewell dinner; held at the Restaurant du Parc des Eaux Vives, that by the following morning my memory of the party was patchy. As always there had been a lot of speeches, including Georges Blaizot's - with an uncalled-for contribution by an intrusive mouse.

Our hosts kept us so well lubricated at the farewell dinner; held at the Restaurant du Parc des Eaux Vives, that by the following morning my memory of the party was patchy. As always there had been a lot of speeches, including Georges Blaizot's - with an uncalled-for contribution by an intrusive mouse.

It was a shame about the mouse, for Georges had written pages of an elegant speech with many a well-turned phrase. Having put on his spectacles, he was proceeding to read it to us when the mouse appeared. The room in which the dinner was held was lit by strip lighting concealed under a border of decorative glass running all the way round the ceiling. The mouse, which had somehow found its way into the space between the glass and the ceiling, apparently decided it would like to join the party. Sharply silhouetted by the lighting, it scampered back and forth above Georges head, occasionally pausing to peer down at the festive scene below. With his eyes on the pages of his speech, Georges read on, happily unaware that the attention of his audience was being diverted elsewhere.

"Une Souris! Regardez!" A half-suppressed titter or two caused Georges to raise his head once, inquiringly. But there were more pages to read, and he pressed on. By then eyes that had been politely concentrated on Georges were gazing upwards at the ceiling. There was discreet pointing, nudges. "Ah, mars la pauvre petite," whispered soft-hearted ladies.

"Oh, the poor little thing! How on earth could it have got up there? The lighting must be singeing its whiskers ... the management should be told …"

Perhaps it was only rodent curiosity; having stolen poor Georges' thunder, the mouse disappeared like a conjuring trick as suddenly as it had appeared, just before Georges brought his speech to an end.

In his report on the Geneva conference Georges paid a generous tribute to Percy's chairmanship. "Thirty questions were on the agenda; all of them were discussed and resolved ... The accomplishment of such a task in such a short time was due to the conduct of the discussions. Tribute for this must first be rendered to the tact and resolution of the Chair ..."

There had been throughout, Georges wrote, "an excellent spirit of amity and cooperation. The league had now become a `fraternite' ..."

SLACES

SLACES